Retrofitting heat pumps

Energy expert Prof. Dr.-Ing. Michael Bauer, a partner at Drees & Sommer, discusses the challenges of the heating transition and the obstacles to the increased use of heat pump technology. He recommends a standardized approach – especially for established residential buildings.

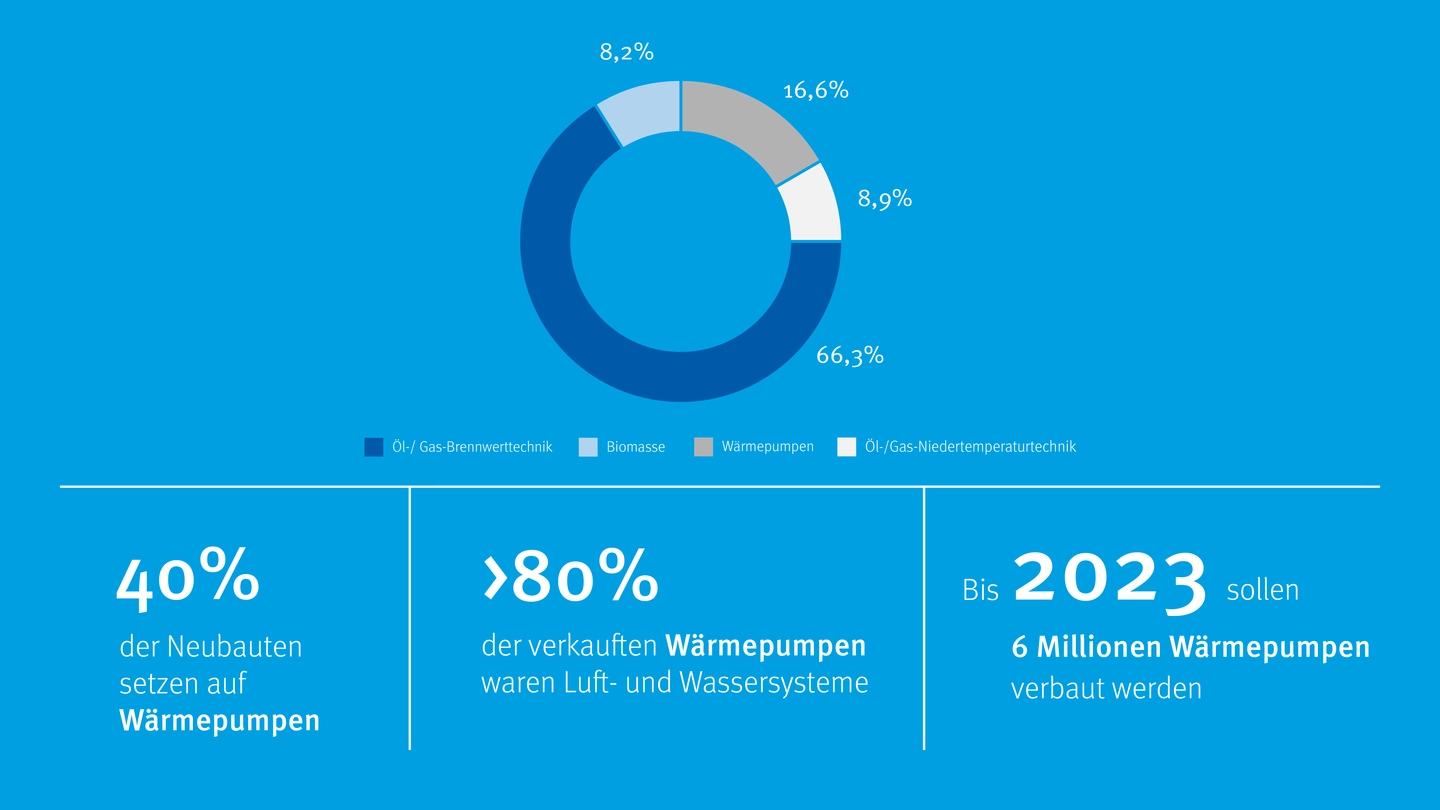

Professor Bauer, the German government wants six million heat pumps to be installed in German residential buildings by 2030 as part of the heating transition. How realistic is that?

Professor Bauer: Up to now the market has not had the necessary know-how. In other words, planners, consulting centers, contractors and customers need to know how existing fossil fuel heating systems can be economically converted to use heat pumps.

So even though we know how to do it in theory, putting it into practice is not that simple?

Exactly. Let me give an example: Each single-family home would first have to be examined in detail to develop an economical solution for it. Generally, small businesses cannot afford to provide this service. It is even beyond the scope of many energy consultants because heat pump technology requires lower operating temperatures than most legacy heating systems, and the questions that need to be answered quickly become quite complex. For example: How does the current heating system operate? How far can operating temperatures be lowered to allow the heat pump to run economically while still providing sufficient heat? What conversions are required? Are storage tanks needed? How cost-efficient are they? What will the whole setup cost? Could photovoltaics be used to improve cost-efficiency? What heat sources are available? Are there any practical alternatives to heat pumps? At the same time, consultants need to familiarize themselves with possible subsidies for heat pumps: Who is entitled to a subsidy? How much is it and for what exactly does it apply? And finally, how economically viable would a heat pump solution be overall?

What do you have to consider when it comes to heat pumps?

- The key problem with heat pumps in established buildings is the large temperature difference between the heat source and the operating temperature of the heating system.

- Possible solutions include lowering the operating temperature of heating systems and selecting a suitable heat source.

- The most commonly used heat sources for heat pumps in residential buildings are outside air, groundwater, geothermal energy, wastewater, and ground loops.

- The cost and benefits must be weighed up when choosing a heat pump and the appropriate heat source.

- Different heating strategies can be adopted depending on the building. For example, a heat pump can be supplemented by a local or district heating network.

That’s enough to make your head spin! Are there no aspects of this technology that are already certain?

Yes, there are. All the necessary technical components are available. And they are also mature. What is missing is sufficient design and operational experience, particularly when it comes to finding the right combination of components in established buildings.

That was my next question: In new buildings, heat pumps are virtually taken for granted. But what is holding back the technology in established buildings?

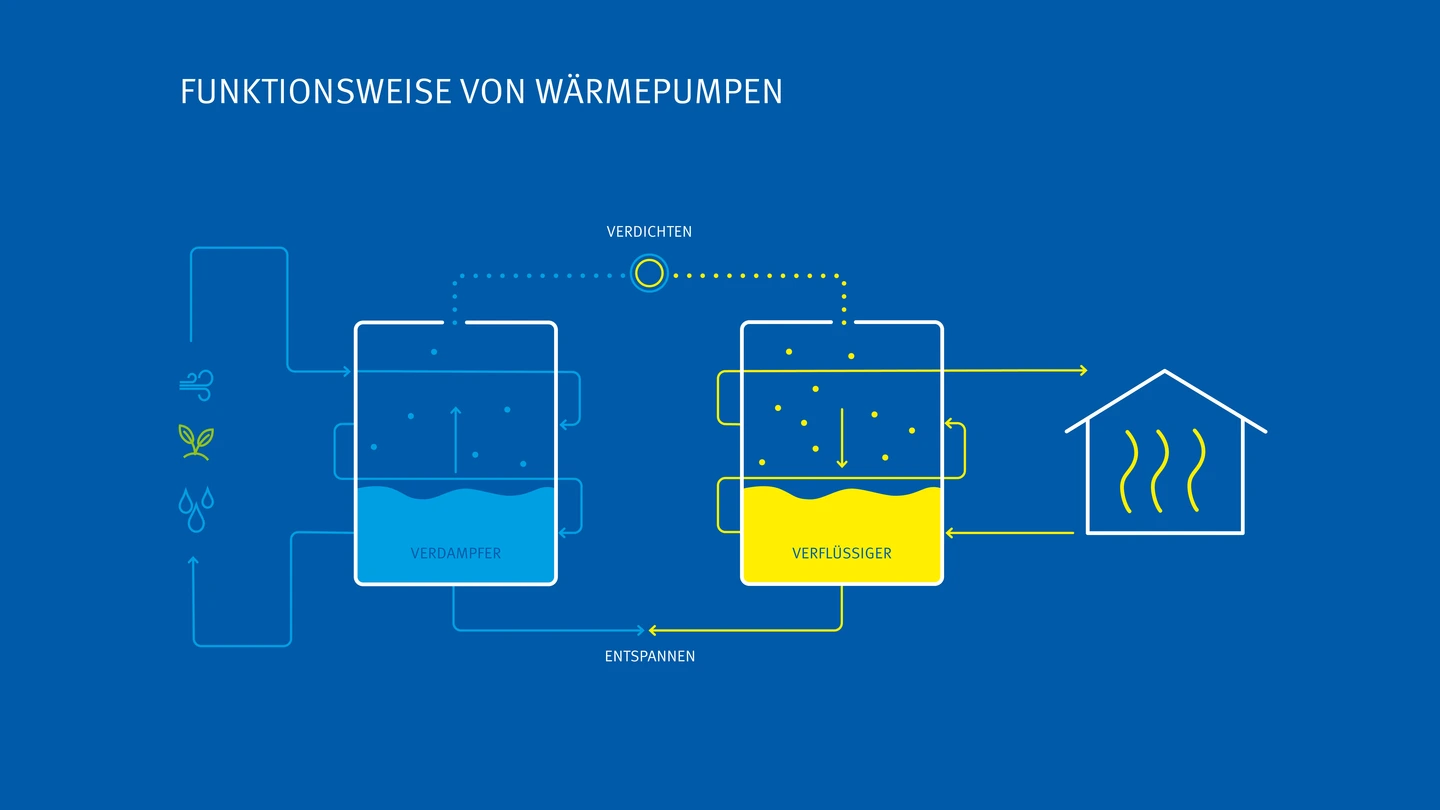

First, I have to explain a basic physical principle of heat pumps: The technology is most effective when the temperature difference between the heat source, such as the outside air or geothermal energy, and the so-called heat sink – that is, the operating temperature of the heating system – is as small as possible.

The problem is that heating systems in established buildings generally have higher operating temperatures than in new buildings – usually around 70 degrees Celsius or higher – which means that the difference between the heat sources and the operating temperature is generally quite high. As a result, the operation of heat pumps in established buildings is usually less economical than in new buildings.

A heat pump uses an external heat source, for example the outside air, to generate heat inside buildings via physical processes - such as the alternate compression and decompression of a refrigerant.

How can the problem be solved?

Firstly, you can try to achieve the highest possible temperatures in the heat source. Using outside air as a heat source is the least favorable option, because in winter the temperature only ranges between about minus twelve and plus five degrees. On the other hand, the installation and operating costs are lower for air-source heat pumps.

Other sources such as geothermal, groundwater, wastewater and the ground loop have higher temperatures of around five to ten degrees. This makes them more efficient, but they are also more expensive to install.

Heat pump types

The type of heat pump used depends on the heat source used. Air-to-water heat pumps use outside or ambient air as a heat source. In the case of water-to-water heat pumps and brine-to-water heat pumps, the thermal energy of the heat source – for example geothermal, groundwater, wastewater, or the ground – is first transferred to a water circuit, and the heat pump then uses the warmed water as a heat source.

The heating system in the established building could also be modified, couldn’t it?

Yes, that’s right. In this case, you have to try to lower the operating temperature without having to undertake expensive conversions. The aim is to ensure that existing heating systems can be operated at a maximum of 55 degrees Celsius. This means you need to analyze how the system operates. The measured data can then be used to determine how far the flow (supply) temperature can be lowered. The further, the better.

It may also be possible to install larger radiators, allowing a lower operating temperature. It is always crucial to weigh up the cost and benefits of all measures.

We always talk about ‘established buildings’. But doesn't that refer to a whole range of very different buildings and building types – from large apartment blocks to single-family homes? How can each of these be quickly analyzed to establish a suitable heating strategy.

It is certainly not easy. Since there is hardly any experience with heat pump technology in established buildings in Germany, the biggest challenge is to develop standard procedures or even standard recommendations for similar buildings as quickly as possible. For example, buildings could be clustered by age or energy efficiency class. Then all the players in the market could use these guidelines instead of reinventing the wheel.

That’s a lot of uncertainty. So what are the basic arguments in favor of heat pumps?

It is clear that heating systems will use electricity and not gas in the future. So property owners have to figure out how to get the most economical electrical heating system possible. Heat pumps are far and away the most efficient solution. One statistic makes this clear: Depending on conditions, a heat pump can generate between three and four kilowatt hours of heat from one kilowatt hour of electricity.

Alternatives such as regenerative local and district heating systems are also good options, depending on the location of the building and on what infrastructure the local authority has in place.

That sounds convincing. But are there any general arguments against a heat pump?

Not really, no. The aim is to develop the most economical and ecologically practical energy concept. Depending on the situation, a heat pump with a storage tank is often the best option. If there are ecologically and economically more viable local heating or district heating connection options, these must be carefully examined.

Overview of the heat generators used in 2021.

Following a decision by the Federal Constitutional Court, the Building Energy Act – popularly known as the Heating Act – will probably not be passed by the Bundestag until autumn 2023. What is your view on the rules the act establishes, such as the date by which heating systems have to be replaced or the minimum proportion of green energy they use? Are such requirements realistic?

I think the government basically has to legislate requirements as a pathway to achieving climate targets. Because, let's face it: Relying solely on voluntary measures has not brought much change in recent decades.

The guidelines that are being discussed, and with which I am so far acquainted, are entirely realistic. For example, heating systems with a share of 65 percent renewable energy can be installed and operated in both new and established buildings. These can be more expensive than comparable fossil heating systems, but gas- and oil-fired heating systems are not future-proof or sustainable from a climate protection or geopolitical point of view. So for me, it is understandable to want to essentially ban them.

But whether industry will be able to meet the demand for appropriate heating systems in the short term is another matter. There may be a temporary shortage of supply of heat pumps, but experience shows that the market quickly adjusts to meet demand.

All in all, there are far-reaching changes ahead for the economy and society. What must property owners and landlords expect in the years ahead?

They should already be looking at how they can transition to a climate-friendly future as economically as possible. To do this, they should have a professional assessment carried out to determine which renewable energy systems are viable options, what conversions are required, and how established buildings can be converted.

For commercial real estate, the EU Green Deal, ESG requirements and the EU Taxonomy provide guidance. But one thing we can say now is that those who do not take action must sooner or later reckon with a loss in value. In the worst case, buildings may become unsaleable. They will become stranded assets.