According to World Bank forecasts, around four billion tonnes of waste will be generated by 2050 - almost 60 percent more than today.* The majority of this will be generated in industrialised countries. No other sector produces more waste than the construction industry. Materials such as concrete, plaster or gravel usually end up in landfill during remodelling or demolition work, even though they are urgently needed for new construction projects and are expensive. The switch to a circular economy should put a stop to this. The problem: "Currently, not even 10 per cent of new and existing buildings are designed for dismantling. In order for seamless recycling to succeed, we first need transparency about what is actually in our buildings and what we can do better to reduce CO2 emissions and primary materials. That's why we need material passports for buildings across the board," says Dr Peter Mösle. As Managing Director of the environmental consulting institute EPEA, a subsidiary of construction and property consultancy Drees & Sommer SE, Mösle and his team design such material passports for all types of buildings. EPEA has now analysed around 50 of these in a unique evaluation and derived important findings for their nationwide design.

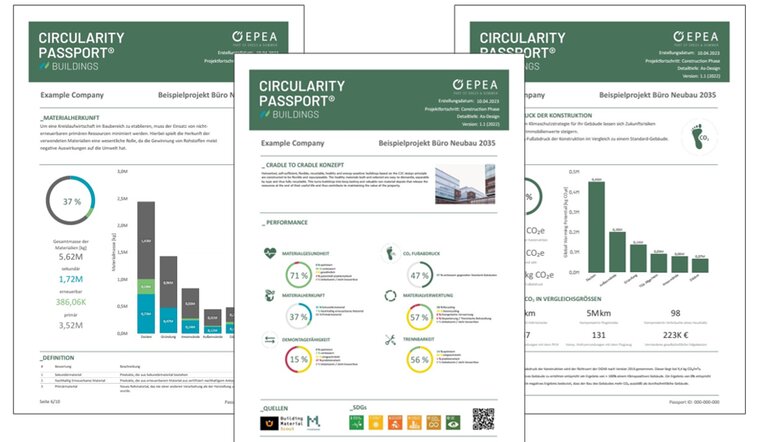

EPEA has been producing material certificates for buildings under the name "Circularity Passport Buildings" for 8 years now. Building owners who already create such a digital building material passport today, as Federal Building Minister Klara Geywitz is also calling for in this legislative period, are anticipating the future. This is because the regulation planned in Europe and Germany will sooner or later force the industry to recycle materials - and to use a building as a raw material store for new buildings when it is demolished. "The introduction of a digital material certificate will change the construction industry as fundamentally as the introduction of the energy certificate 20 years ago, as resource conservation and recyclability will become mandatory criteria in the choice of materials for the first time. To achieve this, we need to harmonise the different models currently available on the market. We are already cooperating closely with the Madaster materials register. However, we absolutely need a legal framework for a uniform standard," demands Peter Mösle.

For Pascal Keppler, Head of Digital Services at EPEA, the categories that a material certificate for a property should definitely include include are as follows: CO2 footprint / life cycle assessment, material types & quantities, proportion of material from renewable or recycled sources, pollutant content, recyclability, separability of materials and the dismantlability of components. As a recycling specialist, Keppler played a key role in developing the resource passports for EPEA. A key result of the evaluation: solid components such as reinforced concrete have the greatest impact on the overall result in the resource passport. "Anyone who opts for RC aggregate, recyclable shoring, low-CO2 cement, reinforcing steel or renewable CO2 storage materials such as wood in their construction project achieves a very good result in the material passport. At the same time, alternative load-bearing structures are no guarantee of good values in the material passport. In order to achieve them, products from manufacturers with high material health and recyclability must also be selected. A pure material type-based optimisation is not sufficient here," says Keppler, summarising key findings from the evaluation.

Birth of the material cards: EU research project BAMB

It all began in 2015 with an EU research project. The project, called BAMB - Buildings As Material Banks, was intended to herald a paradigm shift for the construction industry. For the first time, the focus was on the circular concept for construction products and buildings: "The so-called material cycle of our industrialised society is actually a one-way street," says Pascal Keppler. "Raw materials are mined, processed, used and finally disposed of. In waste management, this is why we talk about downcycling and the cradle-to-grave principle. This contrasts with the cradle-to-cradle approach, according to which we design products from renewable sources in such a way that they can circulate in potentially infinite cycles without any loss of quality."

This is often difficult with conventional building products. In conventional external thermal insulation composite systems, for example, up to 20 different materials are inseparably combined, leaving nothing but hazardous waste behind. Here, raw materials go from the cradle to the grave. On the other hand, there are certified recyclable building materials that not only conserve resources, but also preserve the material value. "At 20 to 30 per cent, a significant proportion of the gross construction costs are in the materials. If the materials used can be recovered at the end of their useful life and then form the basis for new, high-quality products, a significant proportion of this value is retained," says Peter Mösle. However, this is precisely why material certificates are needed - and the financial valuation by the Madaster platform.

Life cycle assessment turns resource graves into raw material depots

Since the EU research project, EPEA has created over 100 resource passports and continuously developed them further. "High scores are awarded if materials either come from renewable sources such as renewable raw materials or if they have already been used as secondary raw materials in construction and are now being given a next life," explains Peter Mösle. He deliberately does not want to refer to this type of reutilisation as recycling. "Current legislation regards downcycling or so-called energy recovery - such as burning wood - as recycling. However, this is poison for climate and resource conservation. That's why we assess materials in the resource passport according to their recycling potential. The assessment takes into account whether we can separate, dismantle and recycle the materials by type during conversion or demolition. We refer to this as industrial reuse." Buildings are thus transformed into valuable raw material depots that release their materials for new projects at the end of their useful life. The CO2 footprint is also analysed in the resource passports. Few people realise that heating, hot water supply and electricity requirements for ventilation and lighting only cause half of the total CO2 emissions in most of today's new buildings. The other half is caused by the production and transport of building materials, including dismantling and disposal. The resource passport also includes this so-called grey energy in order to balance buildings over their entire life cycle.

Resource passport as a planning tool

This information is not only helpful for documentation purposes, but also for environmentally friendly planning. The resource passport shows its optimisation potential particularly in the "material origin" category. As a rule, only some metals - such as reinforcing steel - are produced from secondary materials in new buildings. This corresponds to less than 10 per cent. However, if the resource passport is used to plan the entire life cycle, values of over 40 per cent are already possible today. "The measurable parameters give planning teams the opportunity to optimise their buildings according to aspects of the circular economy," says Pascal Keppler, who helped plan the new Drees & Sommer OWP12 building in Stuttgart using this method.

Almost every beam, every door and even small-scale materials such as adhesives were included in the balancing of the PlusEnergy building on the Drees & Sommer campus. To make such a large amount of information manageable, the data is linked to a digital twin. Clear traffic light colour scales visualise the building products and help to evaluate them before installation. If, for example, the easy separability of materials is not yet or not completely guaranteed, the corresponding component appears in red or yellow. Recyclable components appear in green. The Drees & Sommer building was optimised in this way in accordance with the cradle-to-cradle design principle and received platinum certification from the German Sustainable Building Council in September 2023.

Digital resource passport needs measurable target quotas

The German government is planning to introduce the building resource passport before the end of this legislative period. By then at the latest, the Cradle to Cradle principle will become a prerequisite for subsidies, financing or certification in many places. According to Peter Mösle, such legislation needs one thing above all: clear target quotas modelled on the energy certificate. "Against the backdrop of regulation, the demand for circular design is already on the rise. In order to further boost the raw materials transition, at least 40 per cent of all materials used in construction projects should come from renewable raw materials or secondary materials by 2030 - regardless of whether they are used in new builds or renovations." In existing buildings, this quota can usually be achieved by maintaining the foundations and supporting structures.

For newly designed building materials, Mösle demands a recycling quota without compromise: Everything new must also be able to go back into high-quality cycles later on. "Manufacturers in particular need to adapt their business models by developing their products according to eco-design criteria and practising industrial re-use. This will bring regional added value back to Germany and Europe while reducing our dependence on imported raw materials," says Mösle. "Our ecological problems won't simply disappear by continuing as we are. If we don't want to jeopardise our future, we need to act now and adopt a consistent circular economy based on the cradle-to-cradle principle."

About the report:

Since 2021, EPEA has been balancing all life cycle assessments and circularity passports via an internal database. Due to the diversity and heterogeneity of the projects covered, characteristics were recorded for the quality assurance of the sample. For this purpose, information was collected on the planning status and level of detail of the projects, the scope of the modelling and the type of consulting services. The sample included 48 buildings, 23 of which were office buildings and 14 residential buildings.

Click here for the report: Download report

* Click here for the World Bank report.